Periorbital Cellulitis

Red flags

Compromised vision

Symptoms or signs of meningism

Sepsis

Why is this important?

Permanent loss of vision can occur if periorbital cellulitis is not treated promptly. If the optic nerve is at risk and decompression is not achieved within hours, irreversible damage may occur.

Intracranial complications may occur concomitantly, e.g. meningitis, cavernous sinus thrombosis

When to involve the ENT Registrar

Urgently: Signs of severe disease with eye compromise (chemosis, proptosis, loss of colour vision etc.) - see below

Soon: Signs of moderate disease eg pre-septal cellulitis

Care is normally shared between ophthalmology and ENT (+/- paediatrics), with involvement of neurosurgery if indicated

Who to admit

Always err on the side of caution. Many units would admit patients with any periorbital swelling for a minimum of overnight treatment and observation. Patients with significant swelling or any red flags should be urgently treated, admitted, considered for imaging and kept nil-by-mouth.

Assessment and recognition

Pathophysiology

Photo: right pre-septal (Chandler I) cellulitis. Note how the erythema is clearly confined to the eye lid.

Arising from insect bites or periorbital trauma (including ENT/maxillofacial/ophthalmology procedures): likely to result in pre-septal cellulitis

Arising from sinusitis; fronto-ethmoidal sinus pathology is the usual culprit: more likely to result in orbital cellulitis or abscess

Chandler’s classification gives five different types of periorbital infection (they are not "stages"):

I. Pre-septal cellulitis - cellulitis confined to the eyelids i.e. anterior to the orbital septum

II. Orbital cellulitis without abscess - cellulitis involving the orbit including post-septal tissues

III. Orbital cellulitis with subperiosteal abscess - cellulitis with abscess confined to the orbital periosteum. The abscess is most common based medially on the lamina papyracea but can be elsewhere

IV. Intra-orbital abscess - an abscess in the intraconal compartment (behind the globe between the extra-ocular muscles)

V. Cavernous sinus thrombosis - bilateral periorbital swelling with proptosis, ophthalmoplegia and neurological signs. This has a high mortality and is thankfully rare.

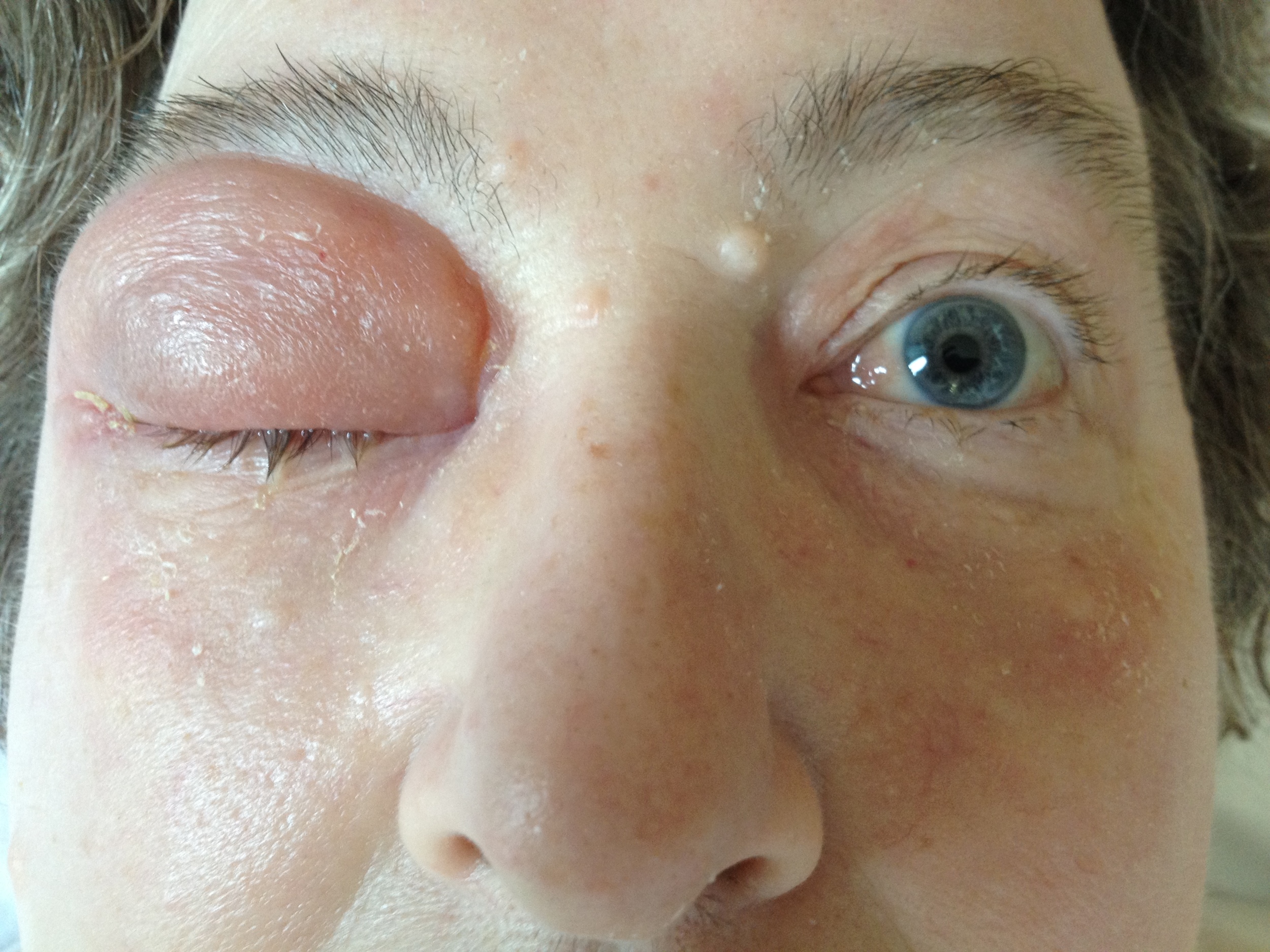

Photo: left post-septal (Chandler II) or orbital cellulitis. Note how the erythema involves the brow, orbit and maxilla.

The three crucial components of the examination are the eye, the nose and neurology.

Eye examination

Whilst the ophthalmologist will provide a more detailed examination, the ENT doctor should have performed a basic eye exam. It is essential to look for any signs of eye compromise. Check for:

Opthalmoplegia/diplopia

Pain on eye movements

Proptosis - look from above the brow

Visual acuity - use a Snellen chart

Colour vision and discrimination - loss of colour vision is a worrying sign and red reportedly goes first; use an Ishihara chart for red/green discrimination

Fundoscopy - engorgement of retinal veins

Nose examination

Nasendoscopy is essential: note the appearance of the nasal mucosa in general and middle meatus area specifically

Any discharge should be swabbed and sent for culture

Neurological examination

A general neurological and cranial nerve examination is essential

Investigations

Send bloods for FBC, CRP, U&E, blood cultures, ABG/lactate (if septic).

A CT orbits/sinuses with contrast is the gold standard in the emergency setting. Imaging should performed urgently if there are any signs of eye compromise (above), if it is not possible to assess the eye due to severe swelling, or if the patient fails to respond to around 24 hours of medical treatment. If a patient has no signs of eye compromise they may be admitted on medical treatment without further investigation, but discuss with your senior if you are unsure.

Immediate and overnight management

Bear in mind the Sepsis Resuscitation Bundle when managing septic patients.

Non-surgical management

Broad spectrum IV antibiotics - consult your local microbiology guidance

Nasal decongestants

Steroid nasal drops

Nasal douches

Supportive: IV fluids, analgesia

Further management

You will need senior input for the following:

Surgical drainage of intraorbital collection:

External-approach drainage (via Lynch-Howarth incision if medial). The most reliable approach in a compromised eye or where access is challenging (e.g. young children).

Endoscopic approach via an ethmoidectomy.

Further imaging may be indicated if the patient fails to progress on medical treatment for 24-36 hours, or if a procedure fails to result in significant improvement.

Page last reviewed: 1 December 2022